BRITISH COMICS

THE VILLAGE UNDER

RED CIRCLE STORY: This episode, taken from The Hotspur issue: 740 January 13th 1951

|

WAS IT A MONSTER? Alan Reader, a Red Circle Second Former,

was among the eight boys from school who were plodding along the road in dim

moonlight. On one side soared jutting crags and fir-covered slopes. On the

other glinted the waters of |

|

MacGregor, wearing his kilt, strode along with Ginger

and Numb Ned. The other Homer, Young Butch, was between Spike Dewey, Captain of

Yank House, and Chris Tansley, the

“What’s that?” he yelled as a dim object swept along

ahead of the swirl. “Great gosh, it looks like a head,” gasped Ginger. It was

an eerie sight to see the “heads,” as Ginger had described it, moving silently

along at a considerable speed. Nobody broke the tense hush until it vanished in

a deep patch of shadow cast by a cliff. Chris looked at MacGregor. “Mac, have

you a monster in the loch?” he asked. “I’ve never heard a whisper about a

monster, though the folk around here are pretty superstitious,” MacGregor

answered. “Well there’s no doubt there was something there, something huge,”

Alan was saying when footsteps were heard. Along the road towards them, coming

into sight round a great buttress of rock, walked a tall, gaunt man. The boys

recognised him. They had seen him fishing. He was staying at the inn near the

castle and MacGregor believed his name was Ressick. “Did you see it?” Ginger

blurted out. “Eh? What are you talking about?” asked Ressick gruffly. “Well, it

seems a bit ridiculous, but we think we’ve seen a monster,” Young Butch said.

Ressick’s taciturn expression gave way to a smile as he heard the story. “I

should say that what you saw was a drifting log—or even a tree,” he said. “It

was moving too fast for that,” MacGregor answered. Ressick looked out across

the loch. “It must have been a trick of the moonlight,” he replied. “Mind you,

I don’t say there isn’t a monster in Loch Ness. I believe that myself—but this

is a new loch. The dam was only finished a matter of three or four years ago,

so where would a monster come from?” “If it hadn’t been moving so fast, I might

have said it was a tree,” MacGregor muttered. “There are some pretty fast

currents in the loch,” Ressick answered. “I can tell you that because I’ve

encountered them when I’ve been out in a boat.” He gave a nod in farewell and

walked on. The boys watching the water, resumed their trek. A mile or so

farther on they reached the spot where the glen narrowed and the dam, gleaming

white in the moonlight, stretched across. The boys went down the steep slope to

the riverbank and after another half-mile, saw dim lights burning in the

windows of the inn and the cluster of adjoining houses. They walked through the

hamlet and came to the gateway leading to the small castle. A log fire was

spurting and crackling in the great hearth in the hall. Mr Thomas MacGregor,

the Home House Captain’s uncle, a burly man of rather over middle-age, welcomed

the belated boys with a smile. “Has our bus broken down again?” he chuckled.

“Yes, Uncle Tom. The back axle went this time,” MacGregor said. “Well, your

walk will have given you an appetite for supper,” replied Mr MacGregor. “We’ve

something to tell you first,” his nephew exclaimed. “We think we’ve seen a monster.”

Mr MacGregor listened keenly as they described the incident. “I can’t agree

with the monster theory, as the loch has only been there a few years,” he said.

“No, I expect it was a tree.” “Well, there’s a way of making sure,” Rob Roy

stated. “We’ll have a look in the morning and see if a tree or a big log has

drifted into the boom.” “Boom?” Alan exclaimed. “Surely you’ve seen the cable

slung across the water above the dam,” Rob Roy said. Oh, yes,” Alan replied,

“but I didn’t know it was a boom.” “It’s there to stop debris reaching the

dam,” Mr MacGregor explained. “The boom stops trees and logs, and later on

they’re towed away.”

“FORM A SEARCH PARTY!”

It was nearly

“Why what’s the matter, M’Pherson?” he asked. “It’s

our Maggie,” said M’Pherson hoarsely. “She’s just home from nightclasses in

Mainport.” He was talking about his daughter, a girl of about eighteen. “She

was coming down the road on her bicycle, Laird, when just past the Eagle Rock

she heard groans down at the side o’ the road. Well, she’s just a lassie and it

gave her a bad fright. She got home just as fast as she could ride.” “Then she

didn’t look down the bank?” Mr MacGregor exclaimed. “No, she was too scared,”

was the answer. “What I’m wondering is if Mr Ressick has met with an accident.”

“We saw him not far from the Eagle Rock,” MacGregor chipped in. “Aye, he said

he’d take a walk after his supper and he hasn’t come back,” said M’Pherson.

“Nice gentleman he is too. He’s down from

THE STEEPLE SQUATTER

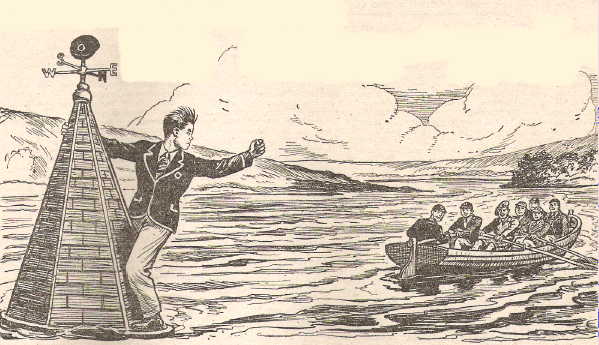

On a grey, damp morning the boys rowed across the loch

in one of Mr MacGregors’s boats to inspect the boom. About four hundred yards

from the dam the cable stretched the full width of the loch. “Umph,” snorted

Numb Ned. “The floating tree theory is wrong. There’s isn’t a sign of a tree.”

Except for twigs and a plank or two, there was nothing caught by the boom. “I

never thought it was a tree,” Alan exclaimed. “It was moving too quickly.”

MacGregor turned to Alan, who was at the tiller. “Bring the boat round, Alan,”

he said. “We’ll head for Eagle Rock now.” Alan did as he was told and the oarsmen,

goaded on by Numb Ned’s remarks, propelled the boat at a fair speed. The old church

steeple was showing above the water and, as he was rather curious. Alan steered

the boat towards it. Seeing the steeple gave Ginger an idea. He had always

regarded himself as pretty good at “hoop-la” and he thought it might be a bit

of a lark if he “capped” the steeple. Not with his own headgear, of course, but

with Numb Ned’s, which happened to be lying on the seat. Before Numb Ned could

move his cap was flying through the air. Ginger’s aim was pretty accurate and

Ned gave a howl of dismay when he saw his cap land perfectly on the steeple

point. Everybody thought it was very funny—everybody, that is, except Numb Ned.

The boat was brought alongside the steeple, and muttering under his breath, the

Fourth Former climbed on to a ledge and started mountaineering for his cap.

Numb Ned stopped muttering and began yelling blue murder when the boys left him

marooned. Five minutes later, however, they yielded to his pleas and he was

taken aboard again. After Ned had accused them of being the worst set of

double-crossing sea-sick sailors, MacGregor was able to get a word in. “We’ll

get along to the Eagle Rock now,” he said. “Will the police have been?” Ginger

asked. “There’s only one policeman on the island—old Sergeant Campbell,” said

MacGregor as they stepped out. “Uncle is going to have another talk with Mr

Ressick before ringing him up.” Moisture was dripping from the trees and the

rocks glistened damply when the boys tied up their boat and hurried along the

road to Eagle Rock. Alan was among the first who went slithering down the bank.

He was close to the spot where they had found Ressick when MacGregor gave a

surprised whistle. “Look at these footprints,” he exclaimed. He pointed down at

footprints left in the mud at the edge of the water. They ended just where they

had found the man lying. “I’ll follow ‘em along and see where they started,”

volunteered Chris. The other boys watched the New Zealander picking his way

along the side of the loch for about fifty yards. Then he turned and climbed

the bank to the road. “That’s where they began,” he called out as he ran back.

“I reckon Ressick must have made those footprints himself,” Young Butch

muttered. “If he did he’s a blooming liar,” said Ginger. “He told us he was

walking down the road when something hit him.” “He didn’t exactly say that,”

Alan blurted out. “He said the last thing he remembered was walking along the

road.” “Yes, he might have forgotten. A smack on the napper can play tricks

with the memory,” said Young Butch. “Just the same, he was down here,” muttered

MacGregor, “and it was here he must have been hit on the head.” “Well, look how

near he was to the water,” Busty piped out. “The monster would have found it

easier to get at him.” Alan’s gaze was attracted by a gleam of metal. He

stooped down and picked something up. “What have you found, Alan!” MacGregor

demanded. “A wrist watch!” Alan said. The wrist watch he passed to MacGregor

was a bit larger than the average and had a substantial steel case. The strap

was a metal jointed strip and it was this that had broken clean through.

“Ressick’s?” MacGregor muttered. “No,” Chris rapped out. “Ressick was still

wearing a wrist watch when we found him. I felt it when I got hold of his wrist

to help him up. MacGregor gave an expressive sniff. “This gets fishier,” he

exclaimed. “First of all Ressick wasn’t on the road when he got his bump and,

second, somebody else was here.” “The man who biffed him?” Young Butch asked.

THE MISSING MAP

Mr MacGregor was in front of the castle when the boys

got back. He was just going to get into the shooting-brake as he was going out

to his farm, ten miles distant. “I’ve seen Mr Ressick and he’s up and about,”

he told them.

“He doesn’t want a fuss made about the incident, but I

thought Sergeant Campbell should know. I rang up his house, but he’s on the

mainland. Have you made any more discoveries?” His intent expression showed his

interest as MacGregor told him the results of their investigations. “I’d like

to get to the bottom of the business,” he said. “I must go to the farm, but as

soon as I get back we’ll go into things again.” Mr MacGregor drove away and the

boys were driven into the castle by heavy spots of rain that fast increased to

a downpour. They had been talking of the mystery for about half an hour when

the sound of a motor engine was heard. “Is your uncle back already?” Chris

asked. MacGregor went to the window. “No,” he said, for it was a small,

battered car that was drawing up at the door. A young man with a sweater under

his coat got out and made a dash through the rain to the steps. MacGregor went

and opened the door. “Come in,” he said. A gruff voice spoke from the car.

“I’ll come in, too, if you don’t mind.” Exclaimed a brawny fellow. “The blarmed

roof’s leaking.” “My name’s Ian Craig,” said the young man who had come to the

door first. Though his name was Scottish he spoke with a Canadian accent. “This

is my friend, George Grant.” The brawny man grinned and gave the boys a nod.

“I’d like to speak to the Laird,” Craig went on. “I’m afraid uncle’s away,”

MacGregor stated. “I’m his nephew if that’s any help.” Craig hesitated. “I’ll

tell you what it is,” he said with a smile. “I’m over here on a vacation from

DEPTH CHARGED!

The boys were in the hall that night when Mr MacGregor

came out of the library. They had heard his phone ring a few minutes

beforehand. “It’s more of a puzzle than ever,” he said. “The police have just

been through from Rocksea.” He named the town on the other side. “Craig and

Grant haven’t landed on the mainland. The coastguards were warned to look out

for them as well. They haven’t been seen.” “Then perhaps they’ve come back to

Mainport,” MacGregor exclaimed. Mr MacGregor shook his head. “They haven’t come

back. I’ve just rung up the harbourmaster,” he said. He went back into the

library, for he had work to do. He left the boys looking thoughtful.

MacGregor's eyes gleamed. “D’you know what I think?” he exclaimed. “I think

they only pretended to go away. They could have left the harbour and then

slipped back on to the island. There are plenty of coves and inlets where they

could have landed. Ginger was by the window. “It’s moonlight,” he said. “How

about a monster hunt?” “What are you going to hunt it with—a harpoon?” asked

Numb Ned. “We’ll go out,” decided MacGregor, “but we won’t be on the loch side.

We’ll climb to the top of the cliffs. We’ll get a better view from up there.”

Half an hour or so later the boys approached the edge of the cliffs near Eagle

Rock from inland. They stood on their lofty lookout and started across the

loch. Time dragged and Young Butch started to stamp his feet. Alan jerked his

head round. “Listen,” he exclaimed tensely and then, to the ears of them all

came the putter of a motor-boat engine. A boat propelled by an outboard engine

nosed into view. It came forging slowly along just below them. Spike pointed to

the man who was crouching in the stern. “Say that’s Ressick,” he muttered.

“What’s he got on his head?” “Phones,” Alan said excitedly. “Earphones…” The

words were hardly out of his mouth when Ressick shoved at the tiller and swung

the boat out towards the middle of the loch. “Gosh, what’s he doing now?”

MacGregor shouted. Ressick stood up in the boat. He lifted his arms high and

seemed to be holding a small cask, or something of that size, in his hands. He

hurled the object away and it entered the water with a splash. Simultaneously he

kicked the helm hard over and the boat swerved away. A fountain of water

erupted from the loch and the muffled detonation of an explosion below the

surface was followed by a tremor that shook the cliff. “My stars,” Young Butch

gasped, “it was a depth charge.” “What’s he trying to kill? The monster?”

gulped Busty. MacGregor’s voice was hoarse with excitement. “Monster be

hanged,” he rapped out. “You use depth charges for hunting submarines!”

NEXT WEEK:

Has Rob Roy hit upon the solution to

Ressisk’s strange behaviour?

Is there a submarine in the loch?

SILENCING THE TELL-TALE

This

episode, taken from The Hotspur issue: 741 January 20th

1951

|

|

|

THE SURVIVORS

The fountain thrown up from

Strange things had taken place on the island since the

eight boys, led by Rob Roy MacGregor, Captain of Home House, had arrived to

spend the Christmas holidays with Rob Roy’s uncle at his castle.

A few nights before, the boys had had a glimpse of

what appeared to be a monster in the loch. Then, later on the same night, Mr

Ressick, a visitor to the island and staying at a nearby inn, had been found

unconscious by the side of the loch, several yards from the road. When Ressick

had recovered he could throw no light on the matter and said the last thing he

remembered was walking along the road. Near

where he had been found, a tree had been snapped off at it’s base, and in the

mud there was a large slithery mark, as if something had crawled into or out of

the loch. The mystery had deepened when an old map of

THE UNDERWATER SEARCHERS

An hour later George Grant sat in front of the fire in

the castle. He had stripped off his oilskins and was wearing a seaman’s jersey

and thick trousers. Craig was suffering from the effects of concussion and had

been put to bed.

Grant, who was still finding hearing difficult, put a

hand to his ear to listen to a question from Mr MacGregor. The boys, with

intense curiosity in their expressions were grouped around. “Why did Ressick

depth charge your submarine?” asked Rob Roy’s uncle. “So it was that murderous

ruffian,” said Grant. “I guessed as much.” A brief grin appeared on his rugged

face. “I’m glad I knocked him out cold last night.” “Then that’s what happened

to Ressick,” Rob Roy exclaimed. “He was lying at the loch side—spying,” growled

Grant. “I happened to catch sight of him just before we hauled the submarine

out of the loch, and I laid him out.” MacGregor spoke excitedly. “You were out

in the submarine last night?” he exclaimed. “Maybe you can tell us what

happened to that tree?” “Yeah,” said Grant. “We put the submarine together over

on the mainland and sailed it across the channel when it was ready. We used a

truck to get it over to Loch Boyne. During the day we kept the sub in the lorry

in a cave. While we were bringing the sub out of the loch the tackle brought down

the tree.” MacGregor frowned thoughtfully. “You only pretended to leave the

island to-day,” he exclaimed. Grant nodded. “That’s right,” he said. “We wanted

Ressick to think we’d gone.” “But you took my map with you and I’d like it

back,” Mr MacGregor snapped sternly. There was no doubting the surprise that

appeared on Grant’s face. “We never took your map, Laird,” he said. “Then who

on earth did take it?” Mr MacGregor demanded. “I could name him,” Grant

retorted. “It’d be Ressick. Probably he saw us come to the castle.” “That would

be possible, uncle,” MacGregor exclaimed. Mr MacGregor shrugged. “We’re getting

nowhere,” he said. “What’s at the bottom of it all?” Grant grinned. “It’s at

the bottom of the lake,” he replied. “It’s Craig’s business, but I’ll tell you.

I’m just giving him a hand. He was my officer when we were serving in

submarines in the Canadian Navy during the war. Great guy he is, too.” Mr

MacGregor raised a hand questioningly. “What are you striving to find in the

loch?” he asked. Grant looked up. “A tombstone,” he said. “The tombstone of Ian

Craig’s great grandfather, Alec Craig of

THE DEAD FISH MYSTERY

Alan was in the castle courtyard in the morning

throwing a ball against the wall and catching it, when Busty came fizzing out

in his energetic way. “Mr Craig is downstairs,” he reported. “He’s much better.

Alan caught the ball and held it.

“What are they going to do now?” he asked. “They’re

going to have a council-of-war when Mr Craig has had his breakfast.” Stated

Busty. “Mr MacGregor has been talking to Mainport on the phone. No one seems to

know if Ressick crossed to the mainland last night or not.” “I reckon he’s

still hanging about,” Alan muttered. “He’d want to make sure he’d sunk the

submarine.” “I wish we’d had a good look at it,” Busty remarked. “I’d have

liked a snap of it,” said Alan, whose Christmas present from home had been a

camera. The lads were tossing the ball about when Mr MacGregor came down the

steps and turned towards the shooting-brake. “I’m just going to the dam,” he

said genially. “The engineer wants to see me about something. Coming with me?”

Alan and Busty nipped into the brake. It was only about a mile to the dam

across the neck of the loch. From the spillway came the thunder of water

released into the river. Tom Finney, the engineer, had been on the look-out for

Mr MacGregor and hurried from the building at the end of the dam. He was a

small wiry

THE UNSEEN HAND

That afternoon the big motor-boat belonging to the dam

chugged slowly out of the creek with the houseboat in tow. MacGregor was at the

helm of the “tug.” His uncle, Ian Craig, Finney, Spike and Ginger were in the

motor-boat. Grant, Alan and the other boys were aboard the houseboat.

They stood on the deck which extended about ten feet

ahead of the cabin, the windows of which were shuttered and the door fastened.

Busty had found that out on thinking he would like a look inside. On the deck

of the houseboat lay the diving suit and equipment, including rubber air-line

on a reel. Mr MacGregor pointed across the loch at a crofter’s cottage on the

far bank. “Set your course for that cottage, Rob,” he said, and his nephew

pushed at the tiller. “Then—he turned and pointed to the end of the loch—” when

we’re in line with the old tower we shall be over the Kirkyard.” On the houseboat

Alan took his camera from his case. He stood just behind the rail at the front

of the craft and started to focus the camera on the motor-boat. Numb Ned

chuckled. “You’ll get a fine picture of the backs of their necks,” he said.

“I’ll give them a call when I’m ready and ask them to turn round,” replied

Alan. The others were all watching him as he brought the view-finder to bear on

the boat. Behind their backs the cabin door opened a few inches. A hand

protruded and there was a flash of steel, the flash of a knife. The hand came

out stealthily and plunged the blade into the air-line coiled on the reel. It

sawed viciously at the rubber tubing. “I’ll give ‘em a shout,” said Young Butch

and raised his voice. “Ahoy there!” The hand was withdrawn and the door closed

as the occupants of the boat looked round to find out what the noise was about.

Alan snapped the shutter and hoped he had a memento of an exciting voyage.

Grant turned towards the middle of the deck. “We’re coming on to our bearings,”

he said. “I’ll get the suit on.” MacGregor brought the houseboat into position

and an anchor, consisting of a ponderous stone on a rope, was sent splashing

down. Finney using his official map, gave the depth of water as twenty feet.

MacGregor edged the motor-boat alongside. The others came aboard the houseboat

and the work went on briskly. A ladder was lashed to the side. Craig fixed the

end of the air-line to the helmet. Grant’s head vanished under the massive

helmet, Finney secured the fastenings, and the rope to the small windlass was

rove round him. With cumbersome movements he worked round on to the ladder and

started to descend. The water gurgled and splashed over Grant’s head. Rope and

tube were played out. His distorted figure looked like a monster in the green

depths. Then he sank out of view. A frantic shout broke from Busty. Alan

whirled round just in time to see the air-line whipping away over the side. It

splashed into the water and started to sink, dragged down by the diver’s

weight. MacGregor leapt on to the rail. There was no time for him to kick off

his shoes before he dived. With his kilt swirling he plunged and vanished under

the surface. Mr MacGregor, Craig and Finney rushed to the windlass to haul up

Grant, but it would take two or three minutes at least to raise him. Alan

watched the surface tensely. It seemed an age before MacGregor’s head broke the

surface. Young Butch let out a hoarse cheer as the Homers’ Captain held up the

end of the air-tube above the water. Thanks to MacGregor’s swiftness Grant was

hauled out without any harm done to him. “That line was under lock and key in

my store,” Finney stated during the grim discussions. “It couldn’t have been

got at there.” “It lay on the bank under the trees while we were loading up,”

Craig exclaimed. “Ressick could have got at it then.” Grant took it calmly.

“There’s plenty of line left for me to go down again,” he said. “We’re in the

right spot. I was in the Old Kirkyard when you hauled me up.”

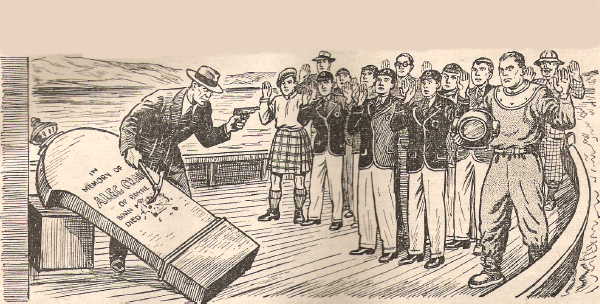

A PHOTO FINISH

An hour later Grant emerged from the loch for the last

time. With his powerful torch he had found the tombstone of Alec Craig and then

secured a chain round it. The bigger boys put their weight on to the windlass

handles. The chain tightened.

“I think it’s moving,” Finney exclaimed. It seemed a long

time to Alan before Craig uttered an excited shout. The shape under the surface

reached the top. The tombstone came slowly out of the water. Busty nearly fell

off the houseboat in trying to see the inscription. “I can’t se,” he began. “I

can’t see ‘In memory of Alec Craig, of

On their way back to

© D. C. Thomson & Co Ltd

Vic Whittle 2006