BRITISH COMICS

THE TOUGH OF THE TRACK

The

following episode of Alf Tupper taken from The Rover No. 1295 - April 22nd

1950

|

|

|

|

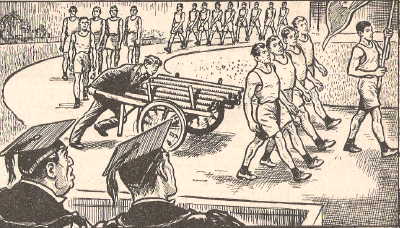

The dignity of

the parade was rudely shattered when Alf Tupper, trundling along a squeaking

wheelbarrow full of jangling pipes, got mixed up with the lines of athletes. |

|

THE GREYSTONE SPORTS

With

a heavy clang, two trucks which were being shunted on the railway viaduct in

Greystone came together, and the impact, shaking the brickwork, fetched down a

shower of flaky sooty whitewash from the roof of the welding shop in the

archway below. Alf Tupper, a lad who was apprenticed to a tradesman called Ike

Smith, at a wage of twenty-five shillings a week, flung off his goggles and

gloves. He leapt up and rushed across the shop. “Look at my blooming shoes!” he

bellowed. “He shook his fist at the roof. “Look at them! I’d like to give that

shunter a smack on the ear.” Ike Smith, who was sitting on an empty box, saw

that Alf was holding up the running shoes that he had polished a little time

previously. “You’ll ‘ave to polish ‘em again,” said Ike quietly. “Polish ‘em

again? I might have had the time if you hadn’t spent the blinking morning

watching me work, instead of lending a hand.” Snapped Alf. “You haven’t got my

rheumatism,” moaned Ike. Alf sniffed. His overalls had holes in them. He needed

a haircut. The state of his fingernails would have caused a manicurist to

swoon. Yet, though he worked in that damp, dark, welding shop, that he also

made his home, because he did not get on with Aunt Meg, he had a great

reputation as an athlete. Alf was crazy about running and jumping, and about

little else—except, perhaps, eating. He was always hungry. Hard work and hard

training accounted for that. Alf had polished his shoes, because on that

Saturday afternoon,

Alf

had been invited because of his reputation as a runner, to take part in the

mile handicap. It was going to be a tough race for the winner. Jack Barstow,

the London champion, and Ian Farne, who had done so well in the Empire Games in

New Zealand, were like Alf, starting off the back mark. Another scratch man was

Paul Shawe, running in the colours of the Granton Hall Athletics Centre,

Greystone, a school that set out to improve the standard of British athletics. Alf

came back across the shop. Ike had received a small order from the Engineering

Department of the University, for welded joints and sections, required for an

extension of the machine room. Alf squatted down and put on his goggles. Ike

rubbed his bristling chin. “Will the job be finished today?” he asked. “What’s

the time?” demanded Alf. “About half-past eleven,” said Ike. “I’ll just about

get done, then,” replied Alf. “Glad to hear it,” muttered Ike. Who could do

with the money. “You’ll be able to take the stuff along to the University first

thing on Monday morning. Alf looked at him scornfully. “D’you think I’m going

to wear my feet out making two trips?” he scoffed “Not likely! I’ll shove ‘em

along in the hand-cart this afternoon on my way to the sports.” At

Alf

hauled open a drawer in the tool bench. He took out a clean shirt. It was full

of wrinkles, because, though he had washed it himself, it had not been ironed.

He tucked the shirt down under his belt that held up his patched trousers.

Round his neck he tied a muffler. He put on a sports jacket that had shrunk

since he had been caught in the rain. Out of the drawer he took a pair of

shorts and a running vest he had brought at a second-hand shop, and which had

the head of a timber wolf on the chest. He wrapped them up in a bit of brown

paper, and put them in the hand-cart with his shoes. He was ready to go. With a

clang and a rattle, Alf shoved the hand-cart, one wheel heeling out crazily,

down the cobbled alley. The first leg of his journey was short. He parked the

hand-cart outside a café in the bottom archway. A smell of fried fish welcomed

him as he pushed open the steamy door. Sam Kessick, the owner of the café,

broke away from a conversation with a tram conductor and a lorry driver. “We’ve

just been talking about you, Alf,” he said. “What chances have you got against

the stars this afternoon?” Alf grinned. “I can run ‘em,” he replied. “Well,

let’s have a stoke-up.” “Fried fish and chips?” asked Kessick. “If you had

turkey and plum pudding. I’d still have fish an’ chips,” said Alf.

THE BOY WITH THE BARROW

Flags

streamed out in the breeze from the flagpoles at the University. The main

buildings formed three sides of the square. On the fourth side was a high wall

and the archway that was the main entrance. A wide drive encircled a big lawn,

in the centre of which was the statue of the Sixteenth Century Founder, Erasmus

Lincoln. Early in the afternoon visitors were arriving in large numbers. As

long as anyone could remember, the sports had opened with an impressive

ceremony in this quadrangle. Clem Johnson, a young reporter, stood on one side

and looked trough the programme with which he had just been presented. He noted

that the ceremony would start with a procession of University dignitaries,

headed by the mace-bearer, to the platform that had been put up in front of the

principal building. When the dignitaries had reached their places, a signal

would be given for the entry of the procession of athletes. Led by the captain

of the University Athletic Club, and followed by four standard-bearers, the

Varsity athletes were to march in through the archway, singing their

traditional Latin song. First they would pass by the platform, salute, march

round again, still singing, and form up in front of the dias for the exchange

of speeches between the captain and the Chancellor of the University. The

latter would then hand a torch to the captain, who would run to the sports

field with it. Maurice Webster, a press photographer, camera bag slung over his

shoulder, walked across to Johnson.

“This

is the tenth time I’m covering this job,” he remarked. “It sound as if they’re just

going to begin,” exclaimed Johnson, as the bells in the tower began to ring.

Into the quadrangle, at a solemn pace, walked the mace-bearer in his cocked hat

and blue tail-coat. The Chancellor, Sir William Gunter, in a wig and scarlet

robes, paced after him. The Principal, Dr Fosdyke, in robes of black and

purple, the Mayor of Greystone, the local M.P.s in top-hats, the professors, in

their hoods and gowns, passed round the quadrangle to the platform. There they

took their seats, looking very dignified indeed. Bugles rang out. As the sound

died away, the procession of athletes started to come under the archway. Louis

Marchant, the captain, a fine figure of a young man in his athletic kit, his

white vest bordered with red, marched like a guardsman. Behind him, the four

standard-bearers wheeled. The words of the Latin song rang out as, in fours,

the procession of athletes swung into the quadrangle. Clem Johnson, who had

seen all this before, was sharpening a pencil, when, out of the corner of his

eye, he saw Webster jerk up his camera. At the same moment Johnson became aware

of a sound that was not musical, and of horrified expressions on the

distinguished faces on the platform. “Gosh! Is this a student gag?” he gasped,

as a jangling, squeaking hand-cart appeared between two squads in the middle of

the procession. Louis Marchant looked over his shoulder, and his face twitched

with fury. With an air of being fed-up to the teeth. Alf shoved the hand-cart

along. At that point there were too many spectators on either side of the drive

for him to push through. The pipes and the angle-irons on his hand-cart banged

and clanged. Ling, a long jumper, who was leading the squad immediately behind

Alf, stopped singing. “Get out of it,” he snapped. Alf glared over his

shoulder. “How can I?” he growled. “I don’t want to be in your procession. I’m

looking for the engineering shop. I was just getting my way in, when you lot

came along with your procession and I got caught in among you.” An angle pipe

fell off the hand-cart. Alf pulled up to pick it up. Ling’s squad divided and

marched round him. He dropped the pipe back on to his load, grabbed the handles

and pushed forward again.

The

Chancellor looked rigidly across the quadrangle at the weathercock above the

archway. The Principal had an aloof expression, as if he had not noticed the

hand-cart. The athletes went on singing. The porter had appeared on the scene.

“Come on out of it!” he cried. “Where’s the engineering place, then?” Alf

snarled. “I’ve shoved these weldings three blooming miles and I want to get rid

of ‘em.” The porter pointed to a passage between two of the buildings. “Take it

away down there!” he snapped. Alf heaved the hand-cart round, and trundled his

load down the passage. The din, if anything was loader because of the echo, but

it gradually died away. The athletes raised their arms in salute. They made

another circuit of the quadrangle and halted in formation in front of the dias.

The Principal bowed to the Chancellor. “Hounoured Sir, in the name of the

members of

THE UNIVERSITY MILE

Half-an-hour

later, Alf had put on his strip in the dressing-room. He found his vest had

shrunk since the previous season, and that every time he straightened himself,

it pulled out of the top of his pants. He was starting to massage his legs,

when the secretary of the Athletic Club, Don Frearson, came into the room. He beckoned to Alf. “We want a word with you

in the committee room!” he snapped. “Okay doke,” grunted Alf, and followed him

along the passage to a room, where Louis Marchant and several members of the

committee were sitting round a table, looking very serious. Marchant scowled at

him angrily. “We have been discussing you, Tupper,” he rapped out. “You ruined

the ceremonies.” “Well, why didn’t somebody tell me where to tip the stuff?”

retorted Alf. Marchant shrugged indignantly. “You wrecked an important

occasion, and we’ve decided to withdraw your invitation to run in the mile

handicap,” he said bleakly. Alf uttered a derisive laugh. He knew that Marchant

was running in the event himself, though not off the back mark. “So you’re

afraid I’ll beat you,” he scoffed. There was an outcry in the room, and

Marchant flushed. “I’m not standing for this,” he shouted. “We shall have

people outside saying the same thing. Let him run.” Alf grinned. “You’d better

stick a rocket in the back of your pants or you won’t have much chance,” he

said. Ten minutes later the runners in the mile invitation handicap were called

to come under the starter’s orders. Ian Farne gripped Alf’s horny hand as they

met going out. “Are you hitting up the knots again, Alf?” he asked. “It’s my

first time out this year,” said Alf.

There

were twenty runners in the race. The man on the front mark was receiving 50

yards start. Marchant was on the 5-yard line. “Get to your marks!” said the

starter. Alf got down between Farne and

The

experts watched keenly, trying to pick out who would try to break away. Alf and

Farne made their effort simultaneously. The Tough of the Track had been nearly,

but not quite, caught out. But they both had to turn out to pass Shawe, and

Alf, on the outside, was a shoulder behind as they straightened. Shawe was

finished. His race had not been well-judged, but from behind came the patter of

A JOB FOR IKE

Alf

stood at the door of the welding shop on the Monday afternoon and shouted

directions to the driver of a Greystone Aviation Company lorry which backed up

the alley. “Straighten out,” yelled Alf. “Okay! Whoa, lad.” Ike Smith stood in

the shop and watched. It was the first time he had received a job from the big

factory. The lorry had brought a load of odd-job parts, mostly small, for

welding. The driver, a chap named Jubb, climbed down. In his lapel was the

badge of the Company’s athletic club. “I never knew you worked here, Alf,” he

said. Alf glanced at Ike. “I’m the only one who does work here,” he replied.

“He ain’t got my rheumatism,” growled Ike. Jubb, who was a keen but not very

good runner, went to the back of the lorry to let down the tailboard. “We shall

be seeing you at our works sports on Saturday,” he said. “Ay, I’m in the

invitation mile,” replied Alf. “If you pull it off you’ll have won the town

double,” remarked Jubb. “You’ll be up against some hot stuff. Jack Barstow’s

coming down, and

While

he held the envelope he had at least a flimsy excuse for not helping with the

unloading. It was a heavy hot job. “Busy up at your place?” Alf asked. “Busy

ain’t the word. That’s why these castings have been sent out,” answered Jubb.

“It’s the hush-hush job that’s keeping us on the hop.” “Hush-hush?” exclaimed

Alf. “You know—the new airliner,” said Jubb. From Ike, who had just opened the

letter came a staggering cry. “Hurt yourself?” Alf asked. Ike’s hand shook.

“They want a batch back every day, Alf,” he gasped. “They want the job finished

off by next Monday.” Alf looked at the pile of castings and pulled a face.

“We’ll just about do ‘em if you take your jacket off and muck in as well,” he

declared.

WHERE IS IKE?

At

half-past six on the Thursday morning a bus conductor going on duty banged on

the door of the welding shop as he went by. After a moment a muffled voice from

inside replied, “Thanks, mate.” Alf lay on a mattress on the floor. For pyjamas

he wore his working shirt and trousers. Old coke sacks were his blankets. He

yawned. As he heaved himself up he heard a rat scuttle away. He felt for his

boots and put them on. He made his way round the shop to the light switch, and

a small lamp burned dimly. The hand-cart was piled up with work done yesterday

to be taken to the works. Alf had a wash and a drink of water. “It’ll be bread

and marge for breakfast this morning,” he muttered. Alf had soon finished his

meagre breakfast. He pulled off his boots and put on a pair of old, cracked gym

shoes and tied the laces. A nearby clock was striking seven as he opened the

door; and, on this cold, misty morning, padded away on a training run. It was

the only bit of time he would be able to snatch all day. Even with Ike lending

a hand for once, they were only just keeping level with the work. In about half

an hour Alf was back and fetching out the hand-cart. Through the stirring city

he pushed it towards the aviation works. A wide, straight road, flanked on one

side by a section of the aerodrome, led to the factory. Alf had to keep into

the gutter. Buses, with their indicators at “special,” motor coaches in from

distant towns, cars, motor-cycles and cycles by the hundred whizzed past him.

The footpaths were full of silent, hurrying figures.

The

two uniformed gatekeepers knew Alf by now, and with a nod, allowed him to pass

through. The factory had as many roads as a small town. Alf pushed the

hand-cart towards one of the doors in the huge aero fitting shop. Managers got

up early as well as employees. Mr Edward Foster, a burly, straight-backed man

of fifty, was standing by the door talking to the bowler-hatted foreman, Fred

Stokes. As Alf stopped, Foster picked up one of the smaller castings and turned

it over in his hand, studying it with a keen, penetrating gaze. “It’s a good

enough job,” replied the manager, and put the casting back on the hand-cart.

Stokes turned to Alf. “Tell your boss to keep the supply up,” he said. “We’re

wanting these as fast as you can deliver ‘em.” “You’ll have ‘em,” replied Alf,

and trudged behind the hand-cart into the factory for unloading. “Did you know

that was the runner, Alf Tupper?” asked Stokes. “Is it?” Foster’s grim mouth

relaxed for a moment. “Then that must be the hand-cart that interfered with the

‘varsity ceremonies. The picture in the paper gave me a laugh.” “He’ll be

running against your nephew at our sports,” said the foreman. Foster had lost

interest, and just grunted. “If I’m wanted I shall be in the top shop,” he

stated. Alf soon came out and pushed along fast with the empty hand-cart. As he

approached the bottom of the alley he saw that a small crowd had collected. A

policeman was in the middle of the throng. “There must have been a smash” Alf

muttered. Then Kessick, who was in the crowd, pointed at Alf. “Here his lad,”

he said. P.C. Hobson parted the crowd by walking to meet Alf. “What have I done

now?” muttered Alf. The constable looked down at him. “When did you see Ike

Smith last?” he asked. “Hasn’t he turned up this morning?” said Alf.

The

policeman’s expression was grave. “He didn’t go home last night,” he said.

“I’ve a cap and coat I’d like you to have a look at.” To the disappointment of

the onlookers, Hobson took Alf into the café, where he picked up a cap and

jacket from a table. Alf nodded. “Yes, they belong to Ike,” he declared.

“That’s bad,” muttered Hobson. “These were picked up on the canal bank. It looks

as if we’ll have to drag for him.”

ALF GETS AN OFFER

On Friday night, at about

Alf lifted his head as if it were

very heavy. “I ain’t knocked off yet,” he said. Coming up to

Mr Foster slowed down as he

approached the alley in his car. The manager had offered to take Alf home. Alf

pushed himself up. “It’s all right,” he said. “I’m just about home. Thanks for

the lift, mister.” Foster stopped and opened the door. “You ran a fine race,”

he exclaimed. “My nephew says he thought he had it in his pocket when you came

up and pipped him. But, you be careful, Tupper. You took too much out of

yourself.” Alf grinned and walked up the alley. Mr Foster had just started the

car when he noticed a pair of running shoes on the floor. He stopped, picked up

the shoes, and got out. He walked up the alley, turned his head, and listened.

It was the unmistakable hiss of a welding torch that he heard. He stepped

forward and a gasp of astonishment broke from him. Alf had already restarted

work. “You needn’t worry about the job, mister,” Alf said. “I’ll have it done

for Monday.” The shoes dropped. Foster stared at the work still to be done. He

thought back. He remembered now seeing a paragraph about Ike Smith’s

disappearance. “Tupper, have you done our work on your own?” he demanded. Alf

sniffed. “Anything wrong with it?” he retorted. “No, there’s nothing wrong with

it,” said the manager. Before going to the sports Foster had happened to notice

the last batch Alf had delivered. He was an engineer through and through. He knew

the time required for each job. “Did you get any sleep last night?” he asked.

“I nodded off now and again,” said Alf. “Sorry I can’t waste time talking,

mister.” Foster turned and walked back to his car. He drove back to the ground.

He searched for Fred Stokes, who was judging the egg and spoon race. When

Stokes had given his decision as to the winner, the manager took him aside.

“Get hold of Alf Tupper when he brings up the last of the work on Monday,” he

said. “He’ll be out of work now that his employer is missing. Offer him a job.

That’s the kind of fellow who can work all night and all day in order to get a

rush job done, then turn out in a mile race, win it, pass clean out, and, on

being taken home, start at once to his work. What a lad!”

The

Tough of the Track (1st series)

32 episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1244 - 1275

The

Tough of the Track (2nd series)

30 episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1295 - 1324

The

Tough of the Track (3rd series) 10

episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1331 - 1340

The

Tough of the Track (4th series) 12

episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1350 - 1361

The

Tough of the Track (5th series) 20

episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1404 - 1423

The

Tough of the Track (6th series) 22

episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1434 - 1455

The

Tough of the Track (7th series) 13

episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1460 - 1472

The

Tough of the Track (8th series)

22 episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1503 - 1524

He’s in

the Army Now (9th series) 31 episodes

appeared in The Rover issues 1543 - 1573

The

Tough of the Track (10th series)

22 episodes appeared in The Rover issues 1646 – 1667

© D. C. Thomson & Co Ltd

Vic Whittle 2003